Chapter 1 Key concepts related to Chemical Reactors Design

In a homogeneous system, the rate of a chemical reaction can be easily estimated because it depends on the temperature system and the concentrations of both reactants and products. However, the prediction on heterogeneous systems is more complicated because of the effect of mass and heat transfer rate over the reaction rate.

1.1 Fundamental of Kinetics and Reaction Equilibrium

It is essential to review some definitions related to design a chemical reactor before starting with our main subject. The first one is reaction rate. For a homogeneous reaction, the reaction rate is defined either as the amount of product formed or the amount of reactant consumed per unit volume of the liquid or gas phase per unit time.

\[\begin{equation*} r \equiv \frac{\text{moles consumed or produced}}{\text{reactor volume} \times \text{time}} \end{equation*}\]

The reaction rate is based on moles of reactant consumed or produced per unit mass of catalyst per unit time for solid-catalyzed reactions.

\[\begin{equation*} r \equiv \frac{\text{moles consumed or produced}}{\text{mass of catalyst} \times \text{time}} \end{equation*}\]

The second important is conversion, \(X\), which is defined as the fraction of the more critical or limiting reactant consumed.

\[\begin{equation*} X_A \equiv \frac{\text{moles A reacted}}{\text{moles of A fed}} \end{equation*}\]

The yield is the quantity created by the desired product compared to the quantity that would have been generated if there were no by-products and the primary reaction was completed.

\[\begin{equation*} Y \equiv \frac{\text{moles of product formed}}{\text{maximum moles of product},\,X=1.0} \end{equation*}\]

For \(nA \rightarrow B\)

\[\begin{equation*} Y \equiv \frac{F_B}{F_A/n} \end{equation*}\]

Finally, the selectivity is the amount of desired product divided by the amount of reactant consumed. This ratio often changes as the reaction progresses, and the selectivity based on the final mixture composition should be called an average selectivity.

For \(nA \rightarrow B\) \[\begin{equation*} \overline{S} = \frac{\text{B formed}}{\text{A used}} = \frac{F_B}{F_A\,X_A/n} = \frac{Y}{X_A} \end{equation*}\]

1.1.1 Power-Law Kinetics

1.1.1.1 Irreversible Reaction

For an irreversible reaction where two reactants forming a product \[\begin{equation*} A + B \rightarrow C \end{equation*}\]

- The overall reaction rate \(r\) can be expressed as the moles of components A being consumed per unit time per unit volume.

- Additionally, the overall reaction rate has a temperature dependence governed by the specific reaction rate \(k(T)\) and a concentration dependence.

In terms of molar concentrations for components \(A\) and \(B\), the overall rate reaction could be expressed as:

\[\begin{equation*} r = k(T)\,C_A^\alpha\,C_B^\beta \end{equation*}\] where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are the order of reaction for each reactants.

The actual reaction mechanism determines the form of the kinetic expression.

- More than one mechanism may provide the same expression of the rate.

- Only in elementary reaction steps the reaction order equal to the stoichiometry.

The temperature-dependent specific reaction \(k(T)\) is represented by Arrhenius equation \[\begin{equation*} k(T) = k_0(T) \exp\left[{\left(-E/R/T\right)}\right] \end{equation*}\] where \(k_0(T)\) is the pre-exponential factor, usually a big positive number that has units with respect to each component based on the concentration units and the order of the reaction, \(E\) is the activation energy, \(R\) is the universal gas-constant, and \(T\) is the absolute temperature.

If \(n = \alpha + \beta\) then \[\begin{equation*} k(T) = \frac{\left[\text{Concentration}^{\left(1-n\right)}\right]}{\text{time}} \end{equation*}\]

It is essential to know that:

- If temperature increase the \(k_0(T)\) will be increased.

- \(k_0(T)\) will be more sensitive to temperature changes at higher activation energy.

1.1.1.2 Reversible Reaction

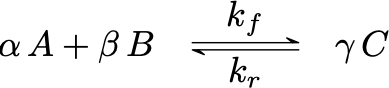

Consider next reversible reaction

The forward rate reaction in terms of molar concentrations of reactants A and B will be: \[\begin{gather*} r_f = k_f(T)\,C_A^\alpha\,C_B^\beta \\ k_f(T) = k_{0_f}(T) \exp{\left(-E_f/R/T\right)} \end{gather*}\]

The reverse rate reaction will be: \[\begin{gather*} r_r = k_r(T)\,C_C^\gamma\\ k_r(T) = k_{0_r}(T) \exp{\left(-E_R/R/T\right)} \end{gather*}\]

The net overall rate reaction will be: \[\begin{equation*} r = r_F - r_R = k_F(T)\,C_A^\alpha\,C_B^\beta - k_R(T)\,C_C^\gamma \end{equation*}\]

Under chemical equilibrium conditions, the net overall rate reaction is equal to zero, which leads to: \[\begin{gather*} K_\text{eq} = \frac{k_f(T)}{k_r(T)} = \frac{C_A^\alpha\,C_B^\beta}{C_C^\gamma} \\ K_\text{eq} = \frac{k_{0_r}(T) \exp{\left(-E_r/R/T\right)}}{k_{0_r}(T) \exp{\left(-E_r/R/T\right)}} = \frac{k_{0_f}}{k_{0_r}}\,\exp\left(\frac{E_r-E_f}{RT}\right) \end{gather*}\]

It is important to know that:

If \(E_R = E_F\), then \(K_\text{eq}\) is independent of temperature

If \(E_R > E_F\), then the process is exothermic, so if temperature increases, then the exponential factor decreases and \(K_\text{eq}\) decreases.

If \(E_R < E_F\), then the process is endothermic (energy is required in order to transform reactants into products), so if temperature increases, then the exponential factor increases, and \(K_\text{eq}\) increases.

The van’t Hoff equation of thermodynamics gives the temperature dependence of the chemical equilibrium constant. \[\begin{gather*} \frac{d\,\ln K_\text{eq}}{d\,T} = \frac{\Delta H_R^\circ (T)}{R\,T^2} \\ \Delta H_R^\circ(T) = E_f - E_r \end{gather*}\]

1.1.2 Multiple Reactions

In a reacting system might occur more than one chemical reaction. We are frequently interested in just one called the principal, while others are side-reactions. The latter produce undesired components that diminish the yield of the desired product.

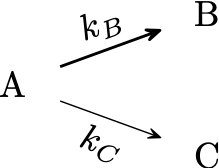

1.1.2.1 Parallel Reactions

In this case, the reactants form other undesired products in parallel with the primary reaction. For example:

If we assume first-order kinetics, the reactions occur in a simple batch isothermal reactor at volume constant. The concentrations of each component could be express as:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{d\,C_A}{dt} &= -\left(k_B+k_C\right)\,C_A \\ \frac{d\,C_B}{dt} &= k_B\,C_A \\ \frac{d\,C_C}{dt} &= k_C\,C_A \end{align*}\]

If at \(t=0\), \(C_A = C_{A0}\), \(C_B=0\) and \(C_C = 0\) then \[\begin{align*} \frac{C_A}{C_{A0}} &= e^{-\left(k_B+k_C\right)\,t} \\ \frac{C_B}{C_{A0}} &= \frac{k_B}{k_B+k_C}\,\left(1-e^{-\left(k_B+k_C\right)\,t} \right)\\ \frac{C_C}{C_{A0}} &= \frac{k_C}{k_B+k_C}\,\left(1-e^{-\left(k_B+k_C\right)\,t} \right) \end{align*}\]

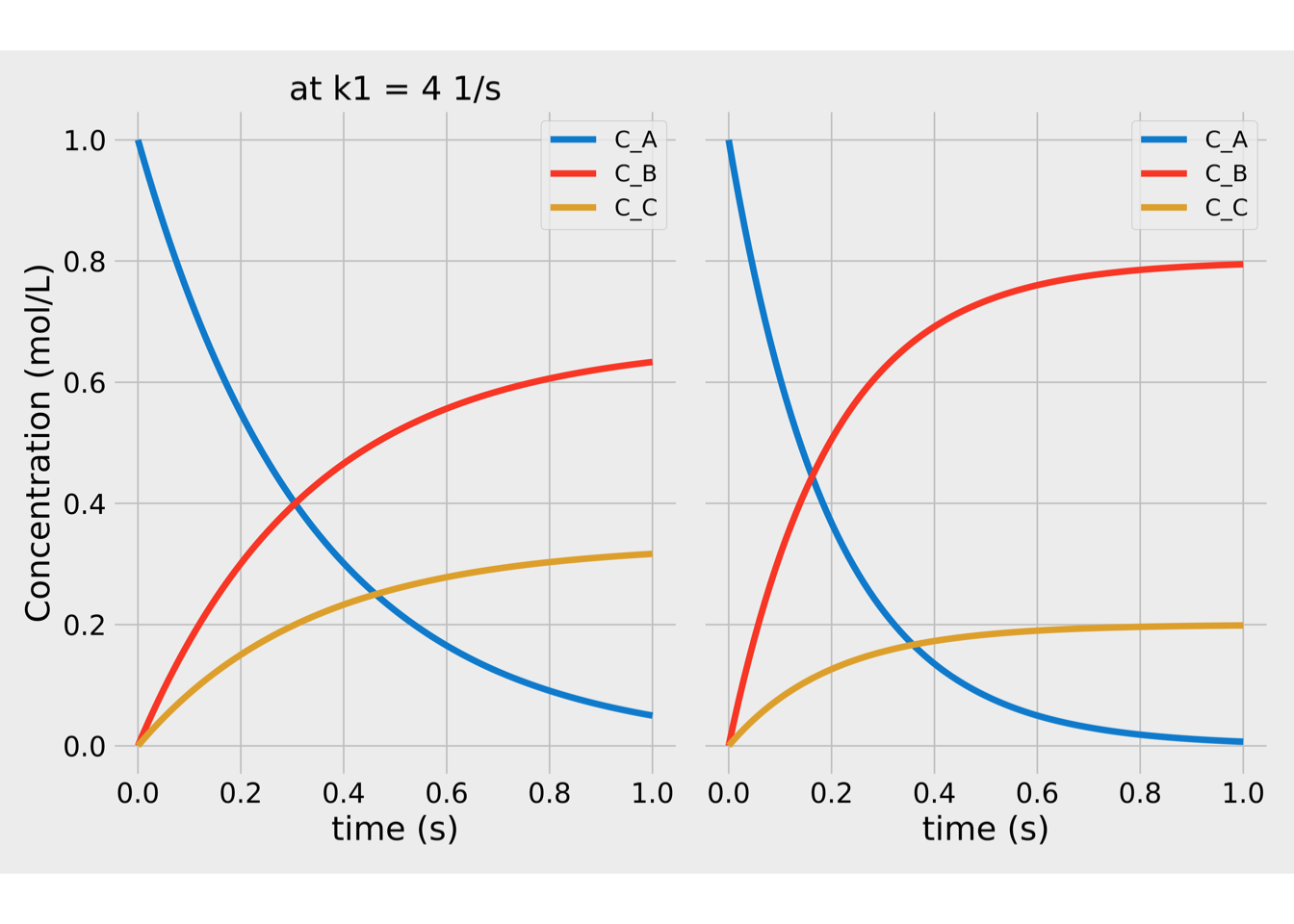

From scypi.integrate, we can use the function solve_ivp to solve ODEs using several Runge-Kutta’s methods.

solution = solve_ivp(fun, (0, tfin), c0,

t_eval=np.linspace(0, tfin, 100))The graphical solution for this sample is available (file).

Figure 1.1: Concentrations vs time for parallel reactions.

In figure 1.1, we could see that more product B is generated at higher \(k_B\) values concerning \(k_C\). This behavior is represented in terms of the Selectivity (S) to the desired product:

\[\begin{equation*} S =\frac{C_B}{C_C} \end{equation*}\]

Our job as engineers is to optimize the reactor’s operation, so in this case, we must find the best operating temperature to maximize selectivity. In the case the reactor has more than one reactant, the selectivity is affected by their concentrations.

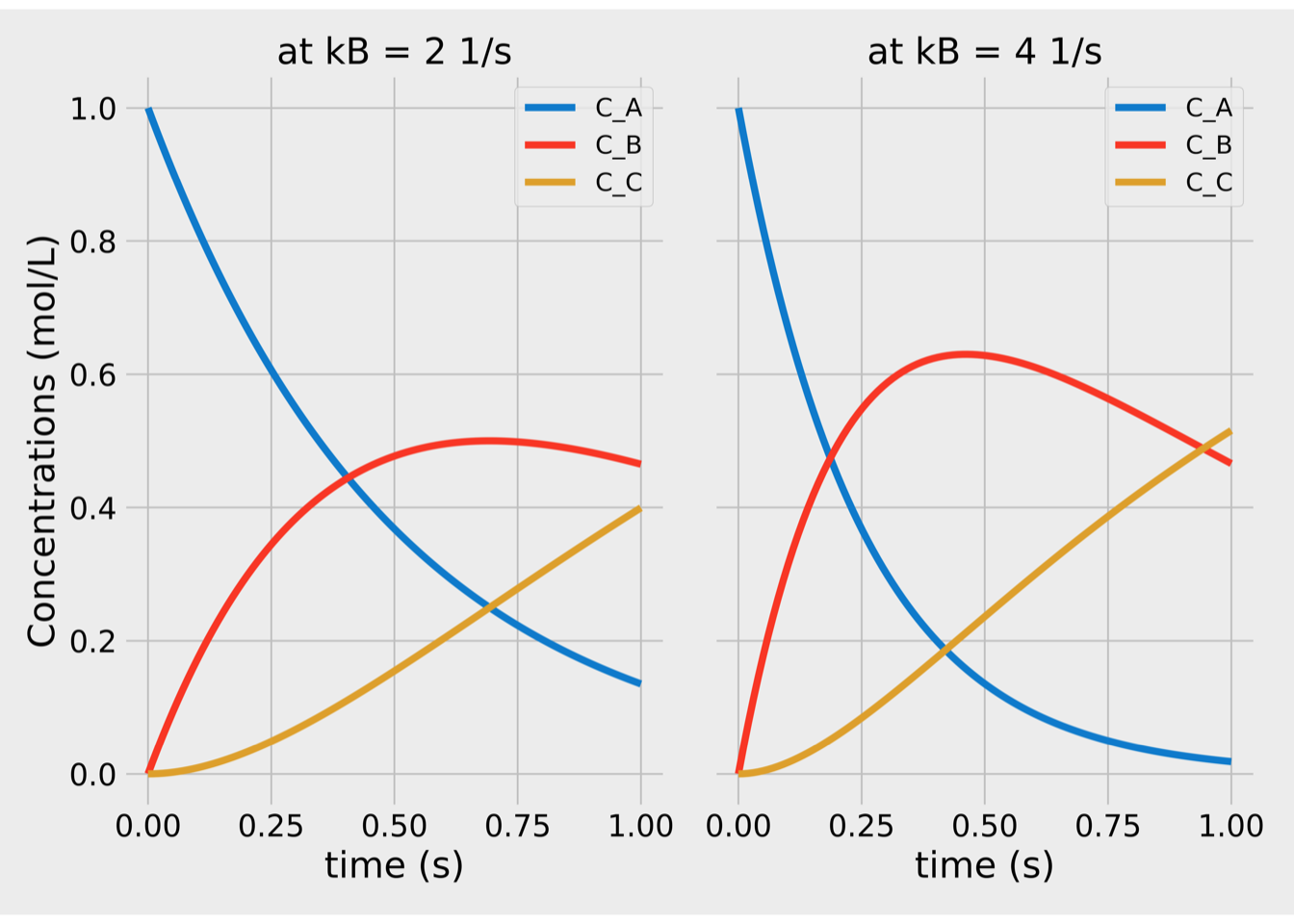

1.1.2.2 Series Reactions

For series reactions, an intermediate is formed that can then further react. For a reaction system:

The reactions in standard form are:

For a batch reactor, the mass balances on A, B, and C are:

\(A \xrightarrow{k_B} B \xrightarrow{k_C} C\)

The reactions in standard form are:

\[\begin{align*} & A \xrightarrow{k_B} B && r_1 = k_B\,C_A \\ & B \xrightarrow{k_C} C && r_2 = k_C\,C_B \end{align*}\]

For a batch reactor, the mass balances on A, B, and C are:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{d\,C_A}{dt} &= -k_B\,C_A \\ \frac{d\,C_B}{dt} &= k_B\,C_A - k_C\,C_C\\ \frac{d\,C_C}{dt} &= k_C\,C_B \end{align*}\]

If at \(t=0\), \(C_A = C_{A0}\), \(C_B=0\) and \(C_C = 0\) then \[\begin{align*} \frac{C_A}{C_{A0}} &= e^{-k_B\,t} \\ \frac{C_B}{C_{A0}} &= \frac{k_B}{k_C-k_B}\,\left(e^{-k_B\,t} - e^{-k_C\,t} \right)\\ \frac{C_C}{C_{A0}} &= 1 -\frac{C_A(t)}{C_{A0}} -\frac{C_B(t)}{C_{A0}} \end{align*}\]

The graphical solution for this sample is available (file).

Figure 1.2: Concentrations vs time for series reactions.

The figure 1.2 shows typical composition profiles. And on the \(C_B\) profile, we notice that there is a peak at some point in time. Therefore, the batch should be stopped at that time to maximize selectivity.

1.2 Temperature effects over chemical kinetics

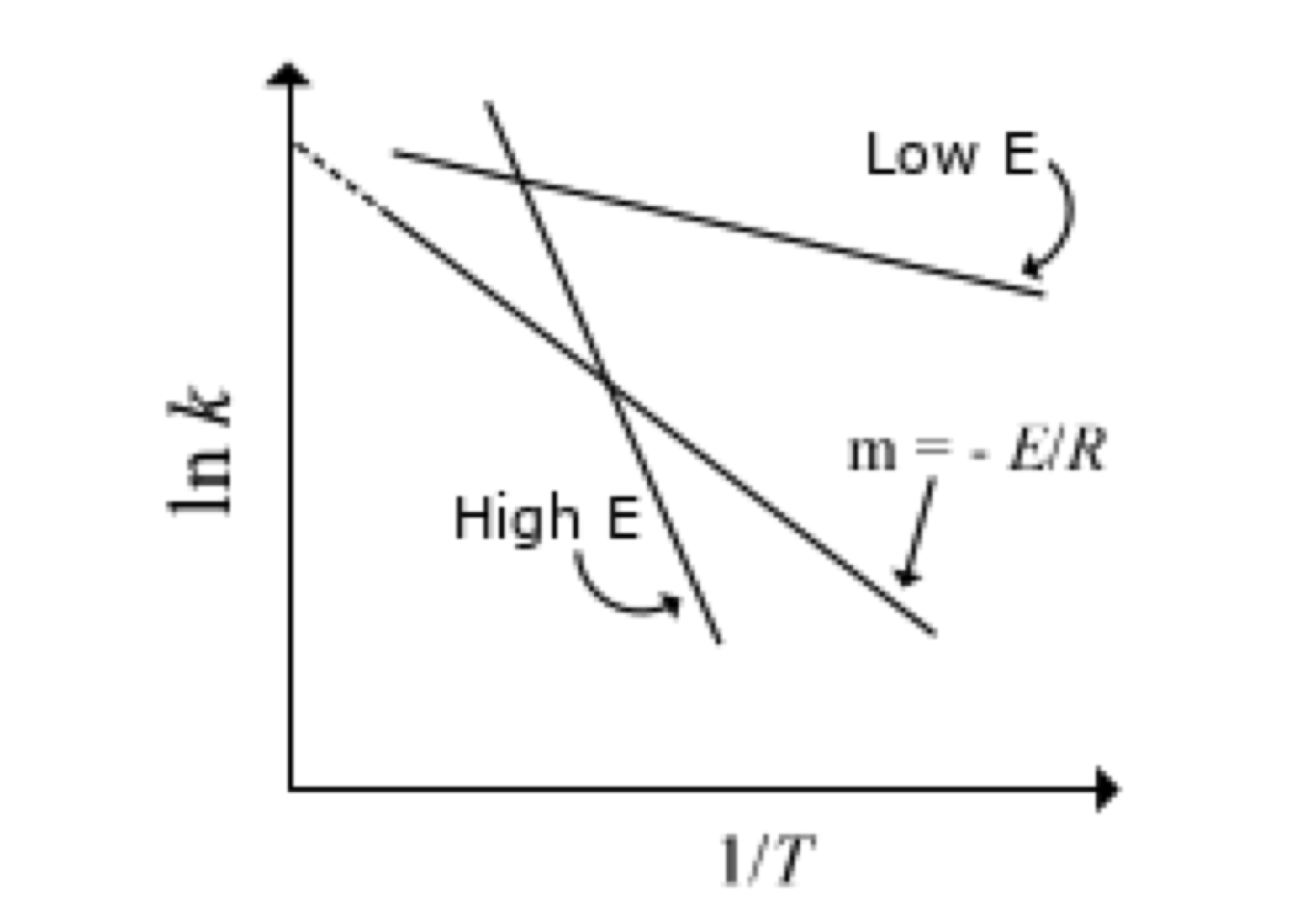

Temperature changes affect the reaction rate, and hence the mode of reactor operation in two ways: temperature dependence of (1) the rate parameters and (2) the equilibrium constant. Several kinds of behavior occur, some of which are represented in fig. @ref(fig:temperature_effect).

The temperature dependence of reactions rate constants will meet the Arrhenius law where A is the pre-exponential factor and E is the activation energy.

Figure 1.3: Typical Arrehnius plot

Whereas the exponential dependence of rate constants on temperature means that the reaction rate changes rapidly as temperature changes. Moreover, the larger the value of activation energy, the more significant the reaction rate difference for a given temperature change.

The temperature dependence of the chemical equilibrium constant (\(K\)) is given by the van’t Hoff equation. \[\begin{equation*} \frac{d\, \ln K}{dT} = \frac{\Delta H_R}{R\,T^2} \end{equation*}\]

Thus for an exothermic reaction, an increase in temperature decreases the equilibrium yield and vice-versa.

![Effect of temperature on reaction rate [@walas1989]](ebook_notes_5314_files/figure-html/temperatureeffect-1.png)

Figure 1.4: Effect of temperature on reaction rate (Walas 1989)

In Figure 1.4, (a) Normal behavior, kinetic rate increases rapidly with rising temperature. (b) The behavior of particular heterogeneous reactions dominated by resistance to diffusion between phases. (c) Typical explosions, where the rapid rise takes place at the ignition temperature. (d) Catalytic reactions are controlled by the rate of adsorption (in which the amount of adsorption decreases at elevated temperatures) and enzyme reactions (where high temperatures destroy the enzyme). (e) Some reactions, such as oxidation of carbon, are complicated by side reaction, which becomes significant as the temperature rises. (f) Diminishing rate with increasing temperature, for example, the reaction between oxygen and nitric oxide where the equilibrium conversion is favored by lower temperatures. The rates appear to depend on the displacement from equilibrium.

The values of the heat of reaction \(\Delta H_{R,j}(T)\) must be known, which must be calculated from

\[\begin{equation*} \Delta H_R (T^\circ) = \sum_i \nu_i \Delta H_{fi}^\circ \end{equation*}\] where the superscript ``\(^\circ\)’’ denotes the standard conditions.

Except in unusual cases, e.g., reactions at supercritical conditions, a temperature correction is the only thing that is necessary to calculate the value of \(\Delta H_{R}(T)\) from \(\Delta H_R (T^\circ)\) using, \[\begin{equation*} \Delta H_{R}(T) = \Delta H_R(T^\circ) + \int_{T^\circ}^T \nu_i C_{Pi}\,dT \end{equation*}\]

Which equation is valid on the assumption that no phase change takes place between \(T^\circ\) and \(T\)

1.3 Equation rate when density of fluid is variable

Changes in the volume yield a difference in concentrations. For example, let us consider the following reaction is taking place in a gas-phase. \[\begin{equation} A + \frac{b}{a} B \xrightarrow{k} \frac{c}{a}C + \frac{d}{a}D \end{equation}\]

At any time, and at any point inside the reactor, it is known that: \[\begin{equation} P\,V = Z\,R\, n\,T \end{equation}\]

Therefore, it is possible to correlate the volume \(V\) at \(t = 0\) with any \(t = t\) by \[\begin{equation} V = V_0 \left(\frac{P}{P_0}\right)\,\frac{T}{T_0}\,\left(\frac{Z}{Z_0}\right)\,\frac{n_T}{n_{T0}} \end{equation}\]

The stoichiometric coefficients in reaction represent the increase in the total number of moles per mole of A reacted by symbol \(\delta\) \[\begin{equation} \delta = \frac{d}{a} + \frac{c}{a} - \frac{b}{a} - 1 \end{equation}\]

Therefore, using this parameter \(\delta\) is possible to calculate the total of moles (\(n\)) at any time t by \[\begin{equation} n = n_0 + \delta \, n_{A0} \, X_A \end{equation}\]

where \(n_0\) represents the total moles at \(t = 0\), \(N_{A0}\) initial moles of \(A\) and \(X\) is the fractional conversion of \(A\).

Combining this relationship with the previous volume equation \[\begin{equation} V = V_0 \left(\frac{P}{P_0}\right)\,\frac{T}{T_0}\,\left(\frac{Z}{Z_0}\right)\,\left(1 + \varepsilon_A\,X_A\right) \end{equation}\]

where \(\varepsilon_A = \delta \, y_{A0}\) and it represents the change in the total number of moles for complete conversion to the total number of moles fed to the reactor.

The concentrations to be substituted into the rate equation can be expressed as \[\begin{equation} C_A = \frac{N_A}{V} = \frac{N_{A0}}{V_0} \frac{\left(1-X_A\right)}{\left(1 + \varepsilon_A\,X\right)} \left(\frac{P}{P_0}\right)\,\frac{T}{T_0}\,\left(\frac{Z}{Z_0}\right) \end{equation}\]

and in terms of the partial pressures, \[\begin{align} P_A & = P \,\frac{N_A}{N} = P\,\frac{N_{A0}}{N_0} \frac{\left(1-X_A\right)}{\left(1 + \varepsilon_A\,X\right)} \\ \notag & = P_{A0}\,\frac{\left(1-X_A\right)}{\left(1 + \varepsilon_A\,X\right)}\left( \frac{P}{P_0} \right) \end{align}\]

When a reactor operates under isothermal conditions, and the pressure drop is neglected, thus \[\begin{equation} V = V_0 \left(1 + \varepsilon_A\,X_A \right) \end{equation}\]

1.4 Ideal Reactors

Industrial chemical reactors can be large and complex pieces of equipment. However, many of these reactors can be modeled with reasonable accuracy using an ideal reactor model. There are two types of ideal reactors, stirred tanks for liquids’ reactions and tubular for gas or liquid reactions.

Stirred-tank reactors include batch reactor, semi-batch reactor, and continuous stirred-tank reactors (CSTRs). The criterion for ideality in-tank reactors is that the liquid is perfectly mixed, which means no gradients in the vessel’s temperature or concentration.

Tubular reactors are considered ideal if there is a plug flow of fluid. There are no radial gradients of concentration or velocity, nor is there no axial diffusion or conduction.

Although these ideal conditions are impossible to reach into real industrial reactors, the classical idealizations can be used for studying both steady-state design and the dynamic control of chemical reactors. In this class, we discuss the classical types of reactors qualitatively: batch reactor (BR), continuous stirred-tank reactor (CSRT), plug flow reactor (PFR).